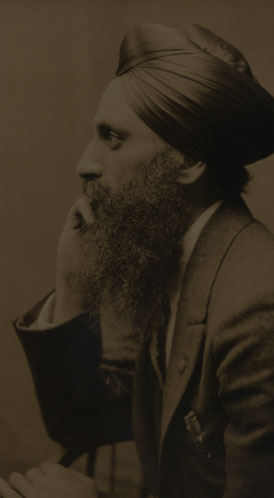

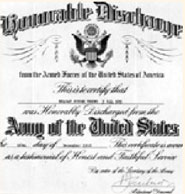

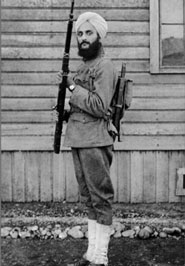

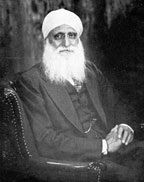

Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind, a native of Punjab, immigrated to America in 1913. In order to pay his way through University of California, Berkeley, he worked in an Oregon lumber mill. He enlisted in the United States Army in 1918, when the United States entered World War I. He was honorably discharged in the same year due to the war ending. In 1920, he applied for citizenship and was approved by the U.S. District Court. The Bureau of Naturalization appealed the case, which made its way to the Supreme Court. Thind’s attorneys expected a favorable decision because the year before in the Ozawa ruling, the same Court had declared Caucasians eligible for citizenship, and Thind was clearly Caucasian. Most North Indians are in fact, Caucasian.

Now the Supreme Court found it necessary to qualify “Caucasian” as being synonymous with “white,” according to the understanding of the common man at the time. Justice Sutherland expressed their unanimous decision, denying Thind citizenship:

“It is a matter of familiar observation and knowledge that the physical group characteristics of the Hindus render them readily distinguishable from the various groups of persons in this country commonly recognized as white. The children of English, French, German, Italian, Scandinavian, and other European parentage, quickly merge into the mass of our population and lose the distinctive hallmarks of their European origin. On the other hand, it cannot be doubted that the children born in this country of Hindu parents would retain indefinitely the clear evidence of their ancestry. It is very far from our thought to suggest the slightest question of racial superiority or inferiority. What we suggest is merely racial difference, and it is of such character and extent that the great body of our people instinctively recognize it and reject the thought of assimilation.”

Because of the Thind decision, many Indians who were already naturalized had their citizenship rescinded. The Thind decision also meant that the Alien Land Law applied to the many Indian immigrants who had already purchased or leased land. After this ruling, some landowners lost their property, but many continued to hold property they had previously acquired. Some chose to buy or lease new property in the names of American lawyers, bankers, or farmers whom they trusted. A few were able to hold land in the names of their American-born children, though this strategy did not become widespread until after a 1933 court case challenging the practice of “Hindu” farmers holding land through American front men. The actual loss of land at the time of the Thind decision is not easy to estimate since official records, of necessity, hid rather than revealed the true owners.

“A change of supreme importance has now come over the world scene, and that is the renascence of Asia. Perhaps, when the history of our times comes to be written, this reentry of this old continent of Asia-which has seen so many ups and downs-into world politics, will be the most outstanding fact of this and the next generation.”

— Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, to an overflow crowd at the Greek Theatre on the University of California, Berkeley campus, 1949

At the time of the Thind decision, some immigrants became discouraged with conditions in the United States and returned to India. But many remained and Pakistani Americans found ways to progress in spite of the many legal and social obstacles of the time.

In India, the British had promised a measure of self-government if Indians would support British efforts in World War I. However, as Dalip Singh Saund describes: “At the conclusion of hostilities, the government of David Lloyd George changed its attitude toward the Indian Nationalists, and instead of fulfilling its promise of self-government for India, instituted a campaign to suppress the nationalist movement.”

In America, the mood was gradually shifting. In the 1920’s, American public opinion, in general, still supported the continued presence of Great Britain in India, though Gandhi’s policies of nonviolence had started to win a following. By the late 1930’s, many Americans began to oppose racism at home and abroad and became receptive to Indian demands for self-government.

Organizations across the country campaigned for Indian independence and for Indians’ citizenship in the United States. The Gadar Party pressed for the independence of India. The Home Rule League, led by Lajput Rai until his death in 1928, campaigned for dominion status. The India Association lobbied vigorously for citizenship. Mubarak Ali Khan, a prosperous Arizona farmer who founded the Indian Welfare League in 1937, worked to build bridges for the people within the American political structure who could influence a decision in favor of Indian citizenship. Sardar Jagjit Singh, a successful New York businessman, fought for Indian independence through the India League of America, formed in 1938. He arranged for Claire Booth Luce’s trip to India, convinced Time magazine to write in support of Indian independence, and lobbied congressmen and diplomats. These combined efforts eventually yielded success. In 1946 the United States Congress passed the Luce-Celler Act, eliminating the ban on Indian immigration and allowing Indians to become naturalized citizens.

Men who had been denied citizenship for decades studied for citizenship exams and took English lessons to pass the English literacy portion. After 1946, immigration from India to the U.S. was still slow (only 100-200 per year), but the loosened restrictions meant that men could now bring wives, children, and other relatives to the United States. Some of the old-timers, as they were now called, whom had remained bachelors even made the trip back to India to marry young wives. The new arrivals brought with them a renewed awareness of Indian customs and religious identities, but they were also challenged by the Indian Americans, who had appropriated much of what they saw as good in their adopted culture and who thought of themselves now as American, as well as Indian.

In 1947, the British finally faced what Indians had known for decades: the time of their departure from India was long overdue. On August 14, 1947, India and newly created Pakistan became independent nations. For the Punjabis in California, the ordeal of Partition was particularly painful because the boundary cut across their home province. However, they also felt great pride in the newly formed nations.

When Prime Minister Nehru visited the United States, he addressed an overflow crowd of 10,000 in the Greek Theatre at Berkeley. A year later, Liaqat Ali Khan, the first Prime Minister of Pakistan, also delivered an address to a huge crowd in the Greek Theatre.

Because of India’s independence, the United States developed an interest in South Asian culture. Second generation South Asian Americans had greater opportunity to explore their heritage, and the general public became interested in the history, religions, and arts of the subcontinent.