Struggle for U.S. Citizenship

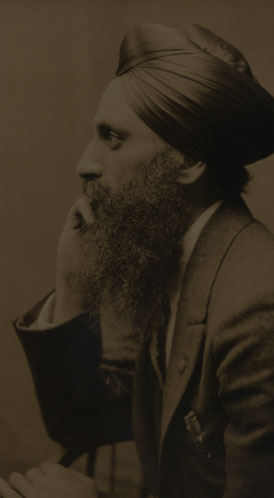

United States citizenship conferred many rights and privileges but only “free white men” were eligible to apply. In the United States, many anthropologists used “Caucasian” as a general term for “white” in absence of any precise definition of the word “white.” Indian nationals from the north of the Indian subcontinent and people from some Middle East countries were also considered Caucasian. Thus, several Indians were granted U.S. citizenship in different states. Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind, subsequent to joining the U.S. army, also applied for citizenship in the state of Washington in July 1918. He received his citizenship certificate on December 9, 1918 in military garb. However, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) did not agree with the district court granting the citizenship. Thind’s citizenship was revoked in four days, on December 13, 1918, on the grounds that he was not a “free white man.”

Thind applied for citizenship again in the neighboring state of Oregon on May 6, 1919. The same INS official who got Thind’s citizenship revoked the first time, tried to convince the judge to refuse citizenship to a “Hindoo” from India. He even brought up the issue of Thind’s involvement in the Gadar Movement, members of which campaigned for the independence of India from Britain. But Thind contested this charge and Judge Wolverton believed him. The judge observed, “He (Thind) stoutly denies that he was in any way connected with the alleged propaganda of the Gadar Press to violate the neutrality laws of this country, or that he was in sympathy with such a course. He frankly admits, nevertheless, that he is an advocate of the principle of India for the Indians, and would like to see India rid of British rule, but not that he favors an armed revolution for the accomplishment of this purpose.” The judge took all arguments and also Thind’s military record into consideration and did not support the INS argument. Thus, Thind received US citizenship for the second time on November 18, 1920. The INS, however, appealed to the the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court for ruling.

Supreme Court Justice George Sutherland delivered the unanimous opinion of the court on February 19, 1923, in which he argued that since the “common man’s” definition of “white” did not correspond to “Caucasian”, Indians could not be naturalized. Shockingly, the very same Judge Sutherland who had equated Whites as Caucasians in U.S. v. Ozawa, now pronounced that Thind though Caucasian, was not “White” and thus was ineligible for U.S. citizenship. He apparently decided the case under pressure from the forces of prejudice, racial hatred and bigotry, not on the basis of precedent that he had established in a previous case.

The Supreme Court verdict shook the faith and trust of Indians in the American justice system. The economic impact for land and property owning Indians was devastating as they again came under the jurisdiction of the California Alien Land Law of 1913 which barred ownership of land by persons ineligible for citizenship. Some Indians had to liquidate their land holdings at dramatically lower prices. America, the dreamland, did not fulfill the dream they had envisioned.

The INS issued a notification in 1926 canceling Thind’s citizenship for a second time. The INS also initiated proceedings to rescind American citizenship of other Indians. From 1923 to 1926, the citizenship of fifty Indians was revoked. The continued shadow of insecurity and instability compelled some to go back to India. The Supreme Court decision further led to a sharp decline in the number of Indians to 3130 by 1930. [From India to America; Garry Hess, p 31]