The ONLY Color Glossy Monthly on West Coast for South Asians

SILICON VALLEY | SAN FRANCISCO | LOS ANGELES | SACRAMENTO | NEW YORK

U.S. HISTORY:

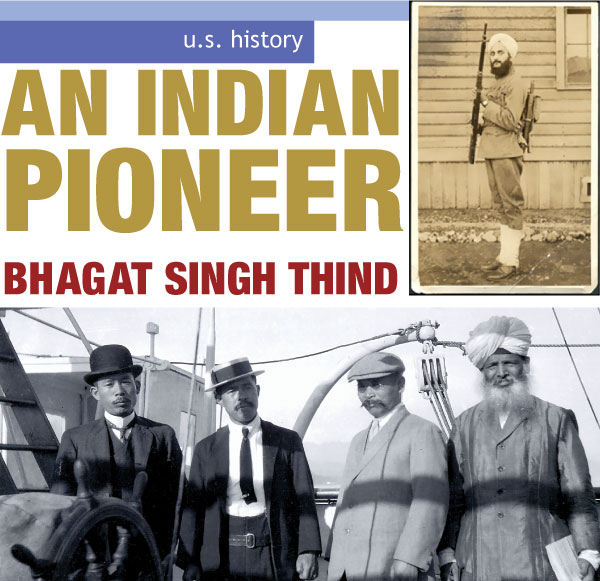

An Indian Pioneer’s Story: Bhagat Singh Thind

Bhagat Singh Thind’s U.S. citizenship was rescinded four days after it was granted. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, where his citizenship was denied due to the color of his skin, writes Inder Singh.

(Inset, top): Bhagat Singh Thind in U.S. Army uniform; (bottom): A Sikh immigrant with other Asian immigrants in Vancouver, BC, circa 1920; (Below): The U.S. Supreme Court, which turned down Thind’s appeal for citizenship on racial grounds.

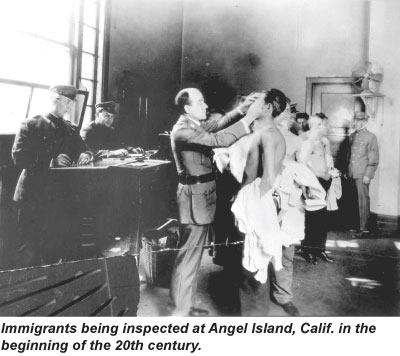

In the annals of Asians’ struggle for U.S. citizenship, Bhagat Singh Thind’s fight for citizenship occupies a prominent historical place. His U.S. citizenship was rescinded four days after it was granted. Eleven months later, he received it for the second time but the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which sent the case to the next higher court for ruling. Thind valiantly fought his case in the U.S. Supreme Court, but the judge revoked his citizenship simply due to the color of his skin. The court verdict in Thind’s case, United States v. Thind confirmed that the rights and privileges of naturalization were reserved for “Whites” only.

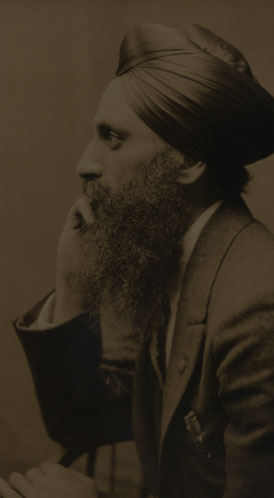

At that time, Indians in the United States were commonly called “Hindoos” irrespective of their faith. Thind’s nationality was also referred to as “Hindoo” or “Hindu” in all legal documents and in the media although he was a Sikh by faith and preserved his religious beliefs by keeping a beard and long hair on his head and wore a turban.

Bhagat Singh was born on October 3, 1892 in Punjab, India. He came to the U.S. in 1913 to pursue higher education. On July 22, 1918, while still an Indian citizen, he joined the U.S. Army to fight in World War I. A few months later in November, Bhagat Singh, a turban-wearing “Hindu,” was promoted to the rank of an Acting Sergeant. He had not even served for a month in his new position when the war ended. He received an honorable discharge in December, 1918, with his character designated as “excellent.”

In those days, U.S. citizenship conferred many rights and privileges but only “free white men” were eligible to apply. In the United States, many anthropologists used Caucasian as a general term for “white.” Indian nationals from the north of the Indian subcontinent were also considered Caucasian. Thus, several Indians were granted U.S. citizenship in different states. Thind also applied for citizenship in the state of Washington in July 1918. He received his citizenship certificate on December, 1918 wearing military uniform as he was still serving in the U.S. army. However, the INS did not agree with the district court granting the citizenship. Thind’s citizenship was revoked in four days, on December 13, 1918, on the grounds that he was not a “free white man.” Thind, as a soldier in the U.S. army, had all the rights and privileges like any “white man” and was worthy of trust to defend the U.S. but America would not trust him with citizenship rights due to the color of his skin.

Thind was disheartened but was not ready to give up his fight. He applied for citizenship again from the neighboring state of Oregon on May 6, 1919. The same INS official who got Thind’s citizenship revoked first time, tried to convince the judge to refuse citizenship to a “Hindoo” from India. He even brought up the issue of Thind’s involvement in the Gadar Movement, members of which campaigned for the independence of India from Britain. But Thind contested this charge. Judge Wolverton believed him and observed, “He (Thind) stoutly denies that he was in any way connected with the alleged propaganda of the Gadar Press to violate the neutrality laws of this country, or that he was in sympathy with such a course. He frankly admits, nevertheless, that he is an advocate of the principle of India for the Indians, and would like to see India rid of British rule, but not that he favors an armed revolution for the accomplishment of this purpose.” The judge took all arguments and Thind’s military record into consideration and declined to agree with the INS. Thus, Thind received U.S. citizenship for the second time on November 18, 1920.

The INS had included Thind’s involvement in the Gadar Movement as one of the reasons for the denial of citizenship to him. Gadar, which literally means revolt or mutiny, was the name of the magazine of Hindustan Association of the Pacific Coast. The magazine became so popular among Indians that the association itself became known as the Gadar Party.

The Hindustan Association of the Pacific Coast was formed in 1913 with the objective of freeing India from British rule. The majority of its supporters were Punjabis who had come to the U.S. for better economic opportunities. They were unhappy with racial prejudice and discrimination against them. Indian students, who were welcomed in the universities, also faced discrimination in finding jobs commensurate with their qualifications upon graduation. They attributed prejudice, inequity and unfairness to their being nationals of a subjugated country. Har Dyal, a faculty member at Stanford University, who had relinquished his scholarship and studies at Oxford University, England, provided leadership for the newly formed association and supported the pro-Indian, anti-British sentiment of the students for independence of India.

Soon after the formation of the Gadar party, World War I broke out in August, 1914. The Germans, who fought against England in the war, offered the Indian Nationalists (Gadarites) financial aid to buy arms and ammunition to expel the British from India while the British Indian troops were fighting war at the front. The Gadarite volunteers, however, did not succeed in their mission and were taken captives upon reaching India. Several Gadarites were imprisoned, many for life, and some were hanged. In the United States too, many Gadarites and their German supporters were prosecuted in the San Francisco Hindu German Conspiracy Trial (1917-18) and twenty-nine “Hindus” and Germans were convicted for varying terms of imprisonment for violating the American Neutrality Laws.

Thind had joined the Gadar movement and actively advocated independence of India from the British Empire. Judge Wolverton granted him citizenship after he was convinced that Thind was not involved in any “subversive” activities. The INS appealed to the next higher court — the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals which sent the case to the U.S. Supreme Court for ruling on the following two questions:

“1. Is a high caste Hindu of full Indian blood, born at Amritsar, Punjab, India, a white person within the meaning of section 2169, Revised Statutes?”

“2. Does the act of February 5, 1917 (39 Stat. L. 875, section 3) disqualify from naturalization as citizens those Hindus, now barred by that act, who had lawfully entered the United States prior to the passage of said act?”

Section 2169, Revised Statutes, provides that the provisions of the Naturalization Act “shall apply to aliens, being free white persons, and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent.”

In preparing briefs for the Ninth Circuit Court, Thind’s attorney argued that the Immigration Act of 1917 barred new immigrants from India but did not deny citizenship to Indians who were legally admitted like Thind, prior to the passage of the new law. He argued that the purpose of the Immigration Act was “prospective and not retroactive.”

Thind’s attorney gave references of previous court cases of Indians who were granted citizenship by the lower federal courts on the grounds that they were “Caucasians.” (U.S. v. Dolla 1910, U.S. v. Balsara 1910, Akhay Kumar Mozumdar 1913, Mohan Singh, 1919). Judge Wolverton, in granting citizenship to Thind, also said, “The word “white” ethnologically speaking was intended to be applied in its popular sense to denote at least the members of the white or Caucasian race of people.” Even the U.S. Supreme Court, in 1922, in the case of a Japanese immigrant, US vs. Ozawa, officially equated “white person” with “a person of the Caucasian race.”

Thind was convinced that based on Ozawa’s straightforward ruling of racial specification and many similar previous court cases, he would win the case and his victory will open the doors for all Indians in the United States to obtain U.S. citizenship. Little did he know that the color of his skin would become the grounds for denial of the right of citizenship by the highest court in the US.

Justice George Sutherland of the Supreme Court delivered the unanimous opinion of the court on February 19, 1923, in which he argued that since the “common man’s” definition of “white” did not correspond to “Caucasian,” Indians could not be naturalized. The Judge, giving his verdict, said, “A negative answer must be given to the first question, which disposes of the case and renders an answer to the second question unnecessary, and it will be so certified.”

Shockingly, the very same Judge Sutherland who had equated Whites as Caucasians in U.S. vs. Ozawa, now pronounced that Thind, though Caucasian, was not “White” and thus was ineligible for U.S. citizenship. He apparently decided the case under pressure from the forces of prejudice, racial hatred and bigotry, not on the basis of precedent that he had established in a previous case.

The Supreme Court verdict shook the faith and trust of Indians in the American justice system. The economic impact for land and property owning Indians was devastating as they again came under the jurisdiction of the California Alien Land Law of 1913 which barred ownership of land by persons ineligible for citizenship. Some Indians had to liquidate their land holdings at dramatically lower prices. America, the dreamland, did not fulfill the dream they had envisioned.

The INS issued a notification in 1926 canceling Thind’s citizenship. The INS also initiated proceedings to rescind American citizenship of other Indians. From 1923 to 1926, the citizenship of fifty Indians was revoked. The Barred Zone Act of 1917 had already prevented new immigration of Indians. The continued shadow of insecurity and instability compelled some to go back to India. The Supreme Court decision further lead to the decline in the number of Indians to 3,130 by 1930.

There probably was little sympathy for treating Hindu Thind shabbily but there was a concern for the poor treatment of the U.S. Army veteran Thind. Thus in 1935, the 74th U.S. Congress passed a law allowing citizenship to U.S. veterans of World War I, even those from the “barred zones.” Thind finally received his U.S. citizenship through the state of New York in 1936, taking oath for the third time to become an American citizen. This time, no official of the INS dared to object or appeal against his naturalization.

Thind had come to the U.S. for higher education and to fulfill his destiny as a spiritual teacher.

Even before his arrival, American intellectuals had shown keen interest in Indian religious philosophy. Among them were author and philosopher Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882), poet Walter Whitman (1819 – 1892), and writer Henry David Thoreau (1817-62).

Emerson had read Hindu religious and philosophy books including the Bhagavad Gita, and his writings reflected the influence of Indian philosophy. In 1836, he wrote about the “mystical unity of nature” in his essay, “Nature.” In 1868, Walt Whitman wrote the poem “Passage to India.” Henry David Thoreau had considerable acquaintance with Indian philosophical works. He wrote an essay on “Resistance to Civil Government, or Civil Disobedience” in 1849 advocating non-violent resistance against unethical government laws. Years later, Mahatma Gandhi adopted a similar methodology, satyagraha, or non-violent protest to defy the law to gain Indian rights in South Africa in 1906. He quoted Thoreau many times in his paper, Indian Opinion.

In 1893, Swami Vivekananda came to Chicago to represent Hinduism at the World Parliament of Religions. He spoke eloquently and made a lasting impact on the delegates. For four years, he lectured at major universities and retreats and generated significant interest in yoga and Vedantic philosophy. He also started the Vedantic Centre in New York City. In 1897, he published his book “Vedanta Philosophy: Lectures on Raja Yoga and other subjects.” The first part of his book included lectures to classes in New York and the second part contained translation and commentary of “Patanjali.”

Swami Vivekananda’s constant teaching, lecturing and addressing retreats increased the number of Americans who became keen to learn about India, Hindu religion and philosophy.

After Swami Vivekananda left, other religious leaders came to fill the void. In 1920, Paramahansa Yogananda came as India’s delegate to International Congress of Religious Leaders in Boston. The same year, he established the Self-Realization Fellowship and continued to spread his teachings on yoga and meditation in the East coast. In 1925, he established an international headquarters for Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles. He traveled widely and lectured to capacity audiences in many of the largest auditoriums in the country such as New York’s Carnegie Hall.

Thind had started delivering lectures on Indian philosophy and metaphysics before Yogananda came here. He was influenced by the spiritual teachings of his father whose “living example left an indelible blueprint in him.” During his formative years in India, Thind read the literary writings of Emerson, Whitman, and Thoreau and they, too, had deeply impressed him. After graduating from Khalsa College in Amritsar and encouraged by his father, he left for Manila, Philippines where he stayed for a year. He resumed his journey to his destination and reached Seattle, Washington, on July 4, 1913.

Bhagat Singh Thind had gained some understanding of the American mind by interacting with students and teachers at the university and by working in lumber mills of Oregon and Washington during summer vacations to support himself while at the University of California, Berkeley. His teaching included the philosophy of many religions and in particular that contained in Sikh Scriptures. During his lectures to Christian audiences, he frequently quoted the Vedas, Guru Nanak, Kabir, and others. He shared India’s mystical, spiritual and philosophical treasures with his students but never persuaded any of them to become Hindu or Sikh. He also made references to Emerson, Whitman, and Thoreau to which his American audience could easily relate to.

Thind offered a new vista of awareness to his students throughout the United States and initiated thousands of disciples into his expanded view of reality. One of his devoted disciples, Rose Elena Davies, introduced her daughter Vivian. Vivian and Bhagat Singh got married in 1940.

Thind, who had earned a Ph.D, became a prolific writer and was respected as a spiritual guide” He published many pamphlets and books and reached an audience of at least several million.

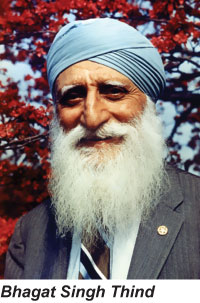

In “Radiant Road to Reality,” Dr. Thind reveals to the seeker how to connect the soul with the Creator. “There are many religions, but only one Morality, one Truth, and one God. The only Heaven is one of conscious life and fellowship with God,” he writes. Thind was working on some books when suddenly he died on September 15, 1967. He was survived by his wife, Vivian, daughter Rosalind and son David, to whom several of his books are dedicated. He never established a temple, Gurdwara or a center for his followers but lived for a long time in the hearts of his numerous followers.

Thind said, “You must never be limited by external authority, whether it be vested in a church, man, or book. It is your right to question, challenge, and investigate.” And he lived his life by that statement. He was a man of indomitable spirit and waged a valiant struggle for citizenship. He extended the boundaries of his fight by challenging prejudice based on race and color.

His son David Thind has established a Web site www.Bhagatsinghthind.com to promote the books and the philosophy for which Dr. Bhagat Singh Thind spent his entire life. He has also posthumously published two of his father’s books, “Troubled Mind in a Torturing World and Their Conquest,” and “Winners and Whiners in this Whirling World.”